The journey to Ouchi-juku felt like peeling back layers of time. As Kenji’s small car navigated the winding mountain roads of Fukushima Prefecture, the modern world gradually receded. Then, rounding a final bend, it vanished entirely. Before him lay a village seemingly plucked from a historical scroll, a perfectly preserved Edo-period post town slumbering in a quiet valley.

The first thing that struck Kenji, a photographer weary of cluttered cityscapes, was the sky. It was vast and unbroken, a clear canvas of blue unmarred by the spiderweb of power lines that usually crisscrossed the heavens. Their absence was more than just visual; it lent an immediate, almost startling authenticity to the scene.

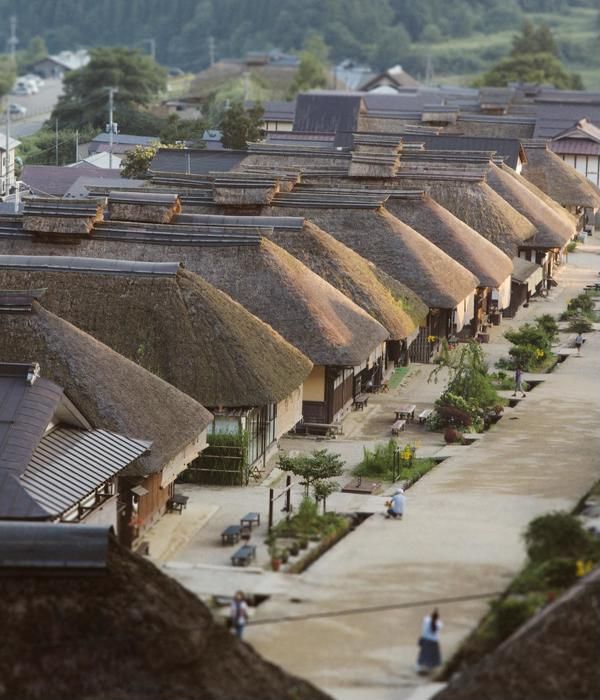

He parked and stepped onto the main thoroughfare, a wide, unpaved street that served as the spine of Ouchi-juku. On either side, more than thirty traditional thatched-roof buildings stood shoulder to shoulder, their deep eaves casting inviting shadows. These weren’t museum pieces behind velvet ropes; they were living structures – guesthouses (minshuku), restaurants serving local delicacies, and artisan shops displaying intricate crafts. The thatch, thick and golden-brown, was layered with an artistry that spoke of generations of skill, each roof a testament to the enduring traditions of the region.

Water, crystal clear, gurgled in narrow channels running alongside the road, a practical and picturesque feature once used for daily needs. Kenji could almost hear the echoes of the past: the clip-clop of horses carrying weary samurai, the chatter of merchants hawking their wares, the hushed tones of daimyos and their retinues resting for the night at a honjin (an officially designated inn) before continuing their arduous journey along the Aizu Nishi Kaido trade route. Ouchi-juku was once a vital artery, a bustling stopover connecting Aizu-Wakamatsu with Nikko.

He paused before a shop selling hand-carved wooden toys and locally woven textiles. An elderly woman with a kind smile and eyes that crinkled at the corners nodded a greeting. “Welcome,” she said, her voice soft. “Take your time. Ouchi-juku does not hurry.”

Indeed, the pace here was different. There was a deliberate calm, a sense of continuity that was profoundly soothing. Kenji wandered further, captivated. He saw no neon signs, no plastic facades, no jarring intrusions of the 21st century. Even the signage was discreet, often beautifully calligraphed on wooden plaques. It was clear that the preservation of Ouchi-juku was not a passive act but a conscious, collective will of its inhabitants to maintain its historical integrity.

Lunch was at a small restaurant renowned for its negi-soba. Instead of chopsticks, he was presented with a long, sturdy Welsh onion (negi) to scoop up the buckwheat noodles from the savory broth. It was a unique, slightly challenging, and utterly delightful experience – another thread connecting him to the town’s quirky, historic customs.

As he ate, he imagined the travelers of old. What stories were shared over bowls of soba in these very rooms? What anxieties about the road ahead, what relief at finding shelter for the night? The thick wooden beams overhead, darkened by centuries of woodsmoke from open hearths, seemed to hold those conversations in their grain.

Later, Kenji climbed the steps to the small Takakura Shrine at the end of the village, which offered a panoramic view. From this vantage point, Ouchi-juku unfurled below him like a perfectly preserved tapestry. The uniform thatched roofs, nestled against the backdrop of verdant mountains, created an image of harmonious beauty. It was easy to see why this place was so cherished. The commitment to keeping the power lines buried, a significant undertaking, was crucial to this immersive experience. It allowed the imagination to roam free, unhindered by modern realities.

As dusk began to settle, paper lanterns (andon) outside the inns and shops flickered to life, casting a warm, inviting glow. The light was soft, gentle, far removed from the harsh glare of city streetlights. The sounds, too, were different: the chirping of crickets, the distant hoot of an owl, the murmur of quiet conversations drifting from behind shoji screens.

Kenji found a room in a charming minshuku. His futon was laid out on tatami mats, the scent of aged wood and straw filling the air. There was electricity, of course, cleverly and discreetly wired, but the feeling was of a simpler time. He lay there, listening to the night sounds of the valley, feeling a profound sense of peace.

Ouchi-juku was more than just a picturesque relic. It was a living, breathing portal to Japan’s past. Its thatched roofs were not just architectural features but symbols of resilience and craftsmanship. The absence of visible power lines was not a mere aesthetic choice but a commitment to authenticity, allowing visitors like Kenji to step fully into a bygone era. He had come seeking photographs, but he left with something far more valuable: a felt connection to history, a reminder of the quiet strength found in preserving the unbroken threads of tradition in a rapidly changing world.

Kenji woke before dawn, the air in his minshuku room cool and still. Outside, a soft mist, common in the valley, was draping Ouchi-juku in an ethereal shroud. He grabbed his camera and slipped out, drawn by the promise of the early light. The village was hushed, the lanterns still casting their gentle glow, but now with a pearlescent halo from the mist. The gurgle of the water channels was the dominant sound, a constant, cleansing presence.

He walked to the far end of the main street, near the Takakura Shrine, and watched as the first hints of sunrise began to paint the eastern sky. The mist swirled, revealing and concealing the thatched roofs in a slow, captivating dance. It felt as if the spirits of the Edo period were still lingering, most tangible in these quiet, liminal hours. He understood then that Ouchi-juku’s magic wasn’t just in its daytime charm, but in these moments of profound stillness, where the veil between past and present thinned.

Later that morning, Kenji struck up a conversation with Mr. Sato, the elderly proprietor of a small shop selling local pickles and handmade crafts. Mr. Sato, his face a testament to a life lived in harmony with the seasons, was mending a traditional straw rain cape (mino).

“These roofs,” Kenji remarked, gesturing towards the beautifully maintained thatch overhead, “they require so much work.”

Mr. Sato nodded, his hands never ceasing their nimble work. “They do. It is a skill passed down, like weaving this mino. Every twenty years or so, each roof needs re-thatching. The whole village helps. It’s called yui, this spirit of cooperation. Without it, Ouchi-juku would not exist as it does.”

Kenji learned that the thatch itself, kaya grass, was harvested from communal mountain fields, another tradition binding the community to the land and to each other. It wasn’t just about preserving buildings; it was about preserving a way of life, a social fabric woven as tightly as the straw in Mr. Sato’s cape.

He asked about the decision to bury the power lines. Mr. Sato chuckled. “That was a big discussion, many years ago. Some said it was too expensive, too difficult. But the elders, they remembered Ouchi-juku before widespread electricity. They knew that to truly keep the feeling of the Edo period, the sky had to be clear. It was for the future, so people like you could come and feel what it was truly like.”

Kenji spent the day exploring the nooks and crannies of the village. He visited the Honjin, the former high-class inn, now a museum, marveling at the intricate woodwork and the subtle elegance of its design, imagining the daimyos who once rested there. He watched an artisan meticulously painting akabeko, the red, bobble-headed cow toys iconic to the Aizu region. He sampled tochimochi, sticky rice cakes made with horse chestnuts, a local delicacy with a unique, earthy flavor.

He noticed the small details: the way the shopkeepers swept their storefronts each morning with traditional brooms, the carefully tended flowers in small pots, the respectful bows exchanged between villagers. There was a deep-seated pride here, not boastful, but a quiet dignity in their role as custodians of this precious heritage.

One afternoon, a group of children, their laughter echoing, ran down the street playing a traditional game with wooden tops. No one shushed them. They were as much a part of Ouchi-juku’s living history as the ancient buildings. Kenji realized that the preservation here wasn’t about freezing time, but about allowing time to flow at its own, more natural pace, where the past informed and enriched the present.

As the days passed, Kenji’s photography shifted. He still captured the iconic views, but he found himself drawn more to the faces of the villagers, the textures of aged wood and worn stone, the play of light in the water channels. He was trying to capture not just the image of Ouchi-juku, but its soul.

On his last evening, he sat by the water channel, the cool air on his face. The lanterns were lit, and the aroma of woodsmoke and cooking food drifted from the houses. He had eaten another memorable meal of negi-soba, this time managing the onion “chopstick” with a bit more finesse. He felt a pang of reluctance to leave. Ouchi-juku had done more than provide him with photographs; it had recalibrated something within him.

He thought about the “unbroken thread” – the unbroken sky thanks to the hidden power lines, the unbroken tradition of thatched roofing and communal help, the unbroken line of people who had lived and worked in this valley for centuries. It was a powerful antidote to the fragmented, often disconnected nature of modern life.

As he prepared to depart the next morning, Mr. Sato pressed a small, hand-carved wooden bird into his hand. “A small piece of Ouchi-juku to take with you,” he said. “So you remember the peace you found here.”

Kenji knew he would. Ouchi-juku, with its steadfast commitment to authenticity, its thatched-roof buildings whispering tales of the Edo period, and its sky free from the visual clutter of modernity, was more than a preserved post town. It was a sanctuary, a testament to the enduring power of community and the profound beauty found when the past is not just remembered, but actively lived and cherished. It was a place where the thread of history remained strong, visible, and deeply inspiring.