The ferry from Ishigaki Island cut through the impossibly turquoise waters of the Yaeyama archipelago, leaving a creamy white wake that dissolved almost instantly into the vibrant blue. Akira, an architect weary of the relentless concrete and glass of Tokyo, felt the tension in his shoulders ease with each nautical mile. His destination was Taketomi Island, a tiny coral cay whispered about in reverent tones for its perfectly preserved Ryukyu village, its iconic water buffalo carts, and a pace of life that seemed to belong to another, gentler era. He sought not just a visual escape, but a deeper understanding of vernacular architecture, of how culture and climate could shape a human habitat into something both beautiful and enduring.

Stepping onto Taketomi’s small pier, the first sensation was the warmth – a soft, humid embrace characteristic of Okinawa’s subtropical climate. The second was the scent of the sea, mingled with the delicate fragrance of tropical flowers and something uniquely earthy. There were no high-rise buildings, no jarring neon signs. Instead, a small cluster of low-slung structures with distinctive red-tiled roofs greeted him, a gentle introduction to the island’s unique aesthetic.

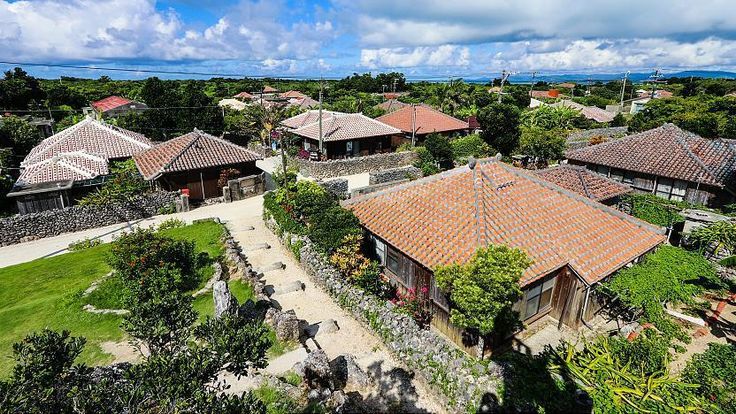

A pre-arranged shuttle, a small van rather than a modern taxi, took him the short distance to the heart of the village. And there it was, a scene that felt both timeless and utterly captivating. The village of Taketomi was a labyrinth of narrow, sandy lanes bordered by walls constructed not of brick or wood, but of rough-hewn pieces of bleached white coral, stacked with an artful, organic precision. These gukku walls, as Akira learned they were called, were porous, allowing the sea breezes to filter through, yet strong enough to offer protection from the occasional typhoon. They were a direct expression of the island’s geology, a building material literally born from the surrounding reefs.

Above these coral walls rose the distinctive red-tiled roofs – akagawara – of the traditional Ryukyu-style houses. The tiles, gently curved and interlocking, glowed a warm terracotta in the Okinawan sun, their vibrant color a striking contrast to the white coral and the lush green of the tropical foliage that spilled over the walls. Each roof was crowned with shisa, fierce-looking lion-dog guardians, believed to ward off evil spirits. Some were comical, some stern, each pair unique, adding a touch of whimsical personality to the otherwise uniform rooflines.

Akira’s guesthouse, Minshuku Takana, was a classic example of this architectural style. A low, single-story wooden structure, its rooms opened onto a shaded veranda that wrapped around a small, sandy courtyard filled with hibiscus and bougainvillea. His host, an elderly woman named Obaasan (Grandma) Kayo, her face a beautiful tapestry of wrinkles earned under the island sun, greeted him with a shy smile and a cup of cool sanpin-cha (jasmine tea).

“Welcome to our slow island,” she said, her Okinawan dialect soft and melodious. “Here, the wind and the stars tell the time.”

Over the next few days, Akira immersed himself in the village. The most iconic mode of transport, and indeed a primary attraction, was the water buffalo cart. He watched, fascinated, as these gentle giants, adorned with flowers, patiently pulled carts laden with smiling tourists through the sandy lanes. The driver, often a local islander, would strum a sanshin (a three-stringed Okinawan banjo) and sing traditional folk songs, their melodies drifting through the quiet air. It wasn’t just a tourist gimmick; it was a living tradition, a nod to a time when these powerful animals were essential for agriculture and transport. Akira took a ride himself, the slow, swaying pace forcing him to observe the village at a different rhythm, to notice the intricate patterns in the coral walls, the way sunlight filtered through the leaves of Fukugi trees planted as windbreaks, the vibrant colors of the flowers blooming in every tiny garden.

The traditional Ryukyu houses themselves were a study in climate-responsive design. Their low profiles and sturdy wooden frames were built to withstand typhoons. The open verandas (engawa) and numerous sliding doors (fusuma and shoji) allowed for maximum cross-ventilation, crucial in the humid climate. The red-tiled roofs, apart from their aesthetic appeal, were heavy and durable. Akira, the architect, spent hours sketching, noting the ingenious joinery, the use of local timber, and the way the houses seemed to sit so lightly on the land, blending harmoniously with their surroundings. There was an inherent sustainability in their design, a wisdom accumulated over centuries of living in tune with the island’s specific conditions.

He learned that the village layout, with its winding, sandy lanes, was not accidental. It was designed to confuse invaders in centuries past and, more practically, to diffuse the force of typhoon winds. The Fukugi trees, planted densely along the lanes and around homes, acted as natural windbreaks and provided welcome shade. Every element seemed to have a purpose, a reason rooted in history, culture, or climate.

Obaasan Kayo shared stories of island life. She spoke of the importance of the sea, which provided sustenance and a spiritual connection for the islanders. She told him about the traditional festivals, particularly the Tanadui seed-sowing festival, one of the most important cultural events, involving sacred rituals, music, and dance to pray for a bountiful harvest. These traditions, she explained, were the threads that bound the community together, passed down from generation to generation.

The “living” aspect of Taketomi was evident everywhere. These were not museum pieces; they were homes. He saw laundry drying on lines in sandy courtyards, heard the distant laughter of children, smelled the aroma of Okinawan cuisine cooking in nearby kitchens. While tourism was undoubtedly a significant part of the island’s economy, it hadn’t overwhelmed the essential character of the village. There was a careful balance, a sense that the islanders were sharing their home, not just selling a product.

One afternoon, Akira rented a bicycle, the other popular mode of transport, and explored beyond the central village. He rode along sandy paths shaded by Fukugi trees, emerging onto pristine white-sand beaches like Kondoi and Kaiji (Star Sand Beach), where tiny, star-shaped grains of sand, the exoskeletons of microscopic marine organisms, could be found. The sea was a dazzling spectrum of blues and greens, the water so clear he could see coral formations and colorful fish just offshore. The natural beauty of the island was as breathtaking as its cultural heritage.

He visited the Taketomi Yugafu-kan, the island’s visitor center and small museum, which provided further insight into the island’s history, ecology, and traditional crafts, such as minsa weaving, a distinctive textile with a pattern of five and four squares, symbolizing “forever and ever” – a traditional gift from a woman to her beloved.

The evenings on Taketomi were magical. As the sun dipped below the horizon, painting the sky in fiery hues, a profound tranquility settled over the village. The only sounds were the chirping of crickets, the distant sigh of the waves, and perhaps the faint strains of a sanshin. With minimal light pollution, the night sky exploded with stars, a brilliant, diamond-studded canopy that felt close enough to touch. Akira would often sit on the veranda of Minshuku Takana, sipping awamori (Okinawan rice liquor) with Obaasan Kayo, listening to her stories, feeling a sense of peace he hadn’t experienced in years.

He realized that the beauty of Taketomi’s village wasn’t just in its individual components – the coral walls, the red-tiled roofs, the water buffalo carts. It was in the harmonious interplay of all these elements, in the way the architecture responded to the climate, the culture reflected the environment, and the community upheld its traditions. It was a holistic system, a living ecosystem of culture and nature.

The coral walls, he mused, were more than just barriers; they were porous membranes, connecting the homes to the island, breathing with the sea breeze. The red-tiled roofs, with their guardian shisa, were more than just shelter; they were expressions of identity, vibrant declarations of Ryukyu heritage. The water buffalo carts, more than just a tourist ride, were a gentle reminder of a slower, more deliberate pace of life, a connection to the island’s agricultural past.

Akira’s sketchbook filled with not just technical drawings, but with impressions of light and shadow, textures of coral and wood, and the vibrant colors of the tropical flora. He began to see how his own architectural practice could learn from Taketomi’s wisdom – the importance of local materials, climate-responsive design, and the creation of spaces that fostered community and a connection to nature.

He observed the meticulous care with which the villagers maintained their homes and the sandy lanes. There was a collective pride, a shared responsibility for preserving the island’s unique character. This wasn’t enforced by strict regulations, but by an ingrained cultural understanding, a deep love for their shima (island).

Before he left, Obaasan Kayo gifted him a small, hand-woven minsa coaster. “So you remember the spirit of Taketomi,” she said, her eyes crinkling at the corners. “Forever and ever, may you find peace.”

As the ferry pulled away from Taketomi, Akira watched the village recede, its red-tiled roofs glowing warmly in the afternoon sun. He carried with him more than just photographs and sketches. He carried the scent of sanpin-cha, the melody of Okinawan folk songs, the feel of cool coral under his fingertips, and the gentle wisdom of Obaasan Kayo. Taketomi Island, with its traditional Ryukyu-style houses, its iconic water buffalo, and its enduring spirit, had offered him a profound lesson in how architecture could be an expression of love – love for the land, love for tradition, and love for community. It was a blueprint for a more harmonious way of living, a design for a life lived in tune with the gentle rhythms of a very special island.