Japan. The Land of the Rising Sun. A country where ancient traditions seamlessly blend with futuristic innovation, where serene temples stand minutes from neon-drenched cityscapes, and where politeness is an art form. For first-time travellers, Japan is an intoxicating, mesmerizing experience. However, this very uniqueness comes with a distinct set of social customs and etiquette that can be bewildering. While the Japanese are famously polite and generally forgiving of well-meaning tourists, knowing what not to do can significantly enhance your experience, help you show respect, and avoid unintentional offence.

Think of this guide not as a list of strict rules designed to intimidate, but as a friendly map to navigate the subtle currents of Japanese society. Mastering these small points of etiquette will not only prevent awkward moments but will also open doors to more meaningful interactions and a deeper appreciation of this fascinating culture. So, pack your bags, charge your camera, and let’s dive into the 12 things you should definitely avoid doing on your first Japanese adventure.

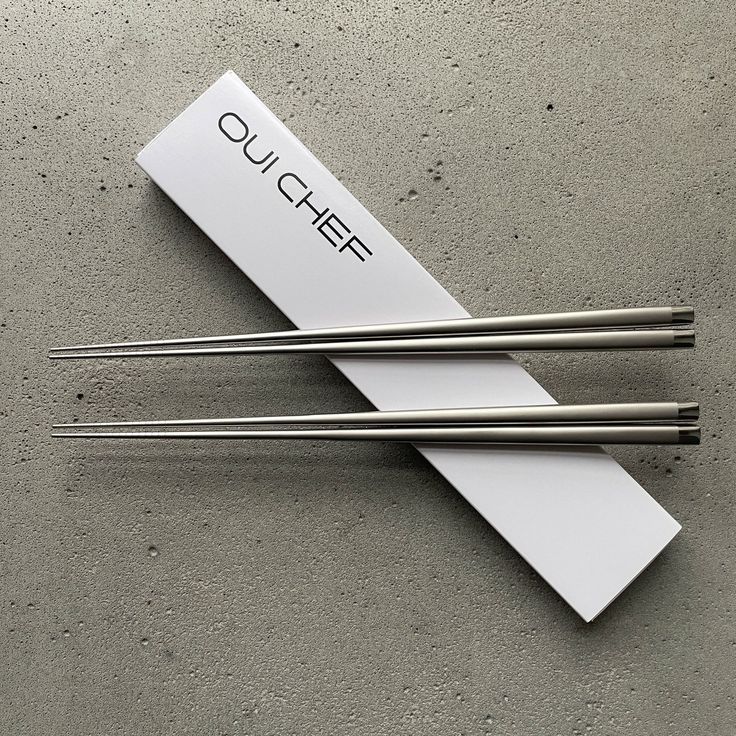

1. The Chopstick Conundrum: More Than Just Utensils

Chopsticks (お箸 – ohashi) are the primary eating utensils in Japan, and their use is steeped in tradition and symbolism. Mishandling them is one of the easiest ways to cause offence, albeit unintentionally.

-

DON’T: Stick your chopsticks upright into your bowl of rice. This is a huge taboo. In Japanese Buddhist funeral rites, a bowl of rice with chopsticks standing vertically is an offering to the deceased. Doing this at a meal is considered extremely unlucky and disrespectful.

-

DON’T: Pass food directly from your chopsticks to another person’s chopsticks. This action mirrors another funeral custom where bone fragments of the cremated deceased are passed between family members. It’s a strong visual and cultural no-no.

-

DON’T: Stab your food with your chopsticks. While tempting with slippery items, chopsticks are not skewers. It’s seen as impolite and unsophisticated.

-

DON’T: Wave your chopsticks around, point with them, or lick them. Treat them with respect, as you would a knife and fork in a formal Western setting.

-

DON’T: Cross your chopsticks on your bowl or table when not in use.

What to do instead:

When not using your chopsticks, place them neatly together on the provided chopstick rest (箸置き – hashioki). If no rest is provided, you can lay them across the top of your bowl, parallel to the edge of the table. When sharing food from a communal dish (if you are explicitly invited to use your own chopsticks), use the opposite, thicker end of your chopsticks to pick up the food, or ask for serving chopsticks (取り箸 – toribashi). If you need to pass food, place it onto a small plate first, then pass the plate.

Understanding these nuances shows consideration and will be appreciated by your hosts or dining companions.

2. The Shoe Shuffle: Where to Wear (and Not Wear) Your Footwear

The Japanese concept of cleanliness distinguishes clearly between “inside” (uchi) and “outside” (soto), and footwear plays a critical role in maintaining this boundary.

-

DON’T: Wear your outdoor shoes inside someone’s home, a traditional ryokan (inn), a temple, or even some traditional restaurants and changing rooms. This is considered unhygienic and deeply disrespectful. The floor, especially tatami matting, is considered a clean living space.

-

DON’T: Step on the threshold (the genkan step) with your outdoor shoes on and then step inside with them. The genkan (玄関) is the entrance area where shoes are removed.

-

DON’T: Wear indoor slippers into the toilet.

-

DON’T: Wear toilet slippers back into the main living or dining area.

What to do instead:

Always look for a genkan or a pile of shoes at the entrance – this is your cue. Remove your outdoor shoes in the genkan, stepping up from the lower “outside” level onto the raised “inside” floor. Point your shoes neatly towards the door for when you leave. You’ll often be provided with indoor slippers.

When you enter a restroom where indoor slippers are worn, you’ll almost always find a separate pair of “toilet slippers” just inside the restroom door. Change into these, and crucially, remember to change back into your indoor slippers when you exit the restroom. Forgetting this is a common, slightly embarrassing, tourist faux pas. When entering a room with tatami mats, you’ll usually remove even your indoor slippers, walking on the tatami in socks or bare feet (though socks are generally preferred for hygiene).

3. Tipping Troubles: The Art of Not Tipping

In many Western cultures, tipping is standard practice, a way to show appreciation for good service. In Japan, this is not the case.

-

DON’T: Tip your waiter, taxi driver, hotel staff, or hairdresser. Good service is expected and is considered part of the job. Attempting to tip can cause confusion and even mild offence, as it can imply that the establishment doesn’t pay its staff adequately or that the service wouldn’t have been good without the prospect of a tip.

-

DON’T: Leave loose change on the table. It will likely be politely returned to you.

What to do instead:

A simple, polite “Gochisousama deshita” (thank you for the meal, it was a feast) after eating, or “Arigato gozaimasu” (thank you very much) in other situations, is sufficient and appreciated. If you truly want to show extra appreciation for exceptional service in a very specific, high-end context (like a private guide you’ve hired for several days or at a top-tier ryokan), any monetary gesture should be presented discreetly in a clean, sealed envelope, never as loose cash. However, for 99.9% of tourist interactions, no tip is the correct approach. Enjoy the freedom from mental tip calculations!

4. Public Volume Control: Keep it Down

Japan values public harmony and consideration for others, which extends to noise levels in public spaces.

-

DON’T: Talk loudly on your mobile phone on trains, buses, or in quiet public areas like temples or museums. This is considered very rude and disruptive.

-

DON’T: Engage in loud conversations with your travel companions in these spaces.

-

DON’T: Play music or videos without headphones.

What to do instead:

Set your phone to silent mode (マナーモード – “manner mode”) when on public transport. If you must take or make a call, be extremely brief and speak in a very low voice, or better yet, wait until you get off. If you’re travelling with friends, keep your conversations at a respectful, low volume. Observe the locals – you’ll notice how quiet public transport generally is. This respect for shared space is a cornerstone of Japanese society. This also extends to eating and drinking on local trains and subways; while generally acceptable on long-distance Shinkansen (bullet trains), it’s frowned upon on commuter trains.

5. Eating and Drinking on the Go: A Pause for Consumption

While convenience stores (konbini) offer a plethora of delicious snacks and drinks, consuming them while walking down the street is generally frowned upon.

-

DON’T: Walk around eating or drinking. This is considered a bit slovenly and can lead to accidental spills or litter.

-

DON’T: Eat or drink on local public transport (subways, local trains). Shinkansen (bullet trains) and long-distance buses are an exception where eating bento boxes is a beloved tradition.

What to do instead:

If you buy a snack or drink from a vending machine or konbini, it’s customary to consume it immediately, either standing to the side near the point of purchase, or at a designated eating area if one is available (some konbini have small seating areas). Once finished, dispose of your rubbish in the bins provided there or carry it with you (more on that later). This habit helps keep the streets remarkably clean.

6. The Nasal Passage Predicament: Blowing Your Nose

This is a small but noticeable cultural difference. Publicly blowing your nose with a loud honk is considered impolite and somewhat unhygienic.

-

DON’T: Blow your nose loudly in public, especially in a crowded train, restaurant, or formal setting.

What to do instead:

If you have a runny nose, it’s more acceptable to sniffle discreetly until you can find a private place, like a restroom, to blow your nose properly. Many Japanese people wear face masks when they have a cold, both to prevent spreading germs and to discreetly manage a runny nose. Carrying a small pack of tissues is always a good idea.

7. Pointing Protocol: The Open Hand Gesture

While pointing with an index finger is common in many cultures, in Japan it can be perceived as aggressive or accusatory, especially when directed at a person.

-

DON’T: Point directly at people with your index finger.

-

DON’T: Use your finger to gesture at objects in a demanding way.

What to do instead:

When gesturing towards a person or an object, use a gentle, open-hand wave in that direction, palm up. If referring to yourself, it’s common to touch your nose with your index finger rather than pointing to your chest. This softer approach is more in line with Japanese non-confrontational communication styles.

8. Onsen & Sento Sanctity: Bathing Etiquette is Key

Public bathhouses (sento) and hot springs (onsen) are an integral part of Japanese culture and a wonderfully relaxing experience. However, they come with strict rules of etiquette, primarily centered around cleanliness.

-

DON’T: Enter the communal bathing pool before thoroughly washing your body. The bath itself is for soaking and relaxing, not for cleaning.

-

DON’T: Wear a swimsuit into the bath. Onsen and sento are traditionally nude experiences.

-

DON’T: Let your small wash towel enter the bathwater.

-

DON’T: Splash, swim, or be rowdy in the bath.

-

DON’T: Enter if you have large, visible tattoos without checking the policy. While attitudes are slowly changing, many establishments still refuse entry to tattooed individuals due to historical associations with yakuza (organized crime).

What to do instead:

Upon entering the changing room, disrobe completely, storing your clothes in a locker or basket. Take only your small wash towel and any toiletries into the bathing area. Proceed to the washing stations (they have stools, faucets, and showerheads). Sit on a stool and scrub yourself thoroughly with soap and rinse off completely.

Once clean, you may enter the bath. The small towel can be placed on your head or set on the side of the bath, but never in the water. Soak, relax, and enjoy the peace. If you have tattoos, check the onsen’s policy beforehand. Some are tattoo-friendly, others may allow you to cover small tattoos with waterproof bandages, or offer private baths (kashikiri-buro).

9. The Great Garbage Quest: Where Are All the Bins?

One of the first things visitors notice is the remarkable cleanliness of Japanese streets, swiftly followed by the distinct lack of public rubbish bins.

-

DON’T: Litter. Ever. This should go without saying, but the lack of bins can be frustrating.

-

DON’T: Expect to find bins conveniently located on every street corner.

What to do instead:

Embrace the local custom: carry your rubbish with you until you find an appropriate place to dispose of it. This usually means taking it back to your hotel or finding bins which are often located near vending machines, inside convenience stores (sometimes specifically for items purchased there), or at train stations (though even these are becoming scarcer). Carry a small plastic bag with you for this purpose. This collective responsibility for cleanliness is deeply ingrained.

10. Photography Permissions: Click with Consideration

Japan is incredibly photogenic, but it’s important to be mindful when taking pictures, especially of people and sacred or private places.

-

DON’T: Take photos of people up close without their explicit permission. This is a matter of privacy and respect.

-

DON’T: Take photos inside temples, shrines, or museums where signage explicitly prohibits it. Often, photography is allowed on the grounds but not inside main prayer halls or specific exhibits.

-

DON’T: Use flash photography where it’s disruptive or disallowed.

-

DON’T: Photograph private homes or geishas/maikos without discretion and permission. While geishas in areas like Gion in Kyoto are a common sight, they are often on their way to appointments. Crowding them or aggressively taking photos is highly discouraged.

What to do instead:

Always look for “no photography” signs. If you wish to take a picture of someone, a polite gesture with your camera and a smile can often convey your intention. If they decline, respect their wishes. For scenic shots, be aware of your surroundings and avoid blocking pathways or being intrusive. When in doubt, err on the side of caution and politeness.

11. The Language Barrier: Don’t Assume English Fluency

While English proficiency is growing, especially in major tourist hubs and among younger generations, it’s not universally spoken.

-

DON’T: Assume everyone you meet will understand English fluently.

-

DON’T: Speak too quickly or use complex slang or idioms when trying to communicate in English.

-

DON’T: Get frustrated if someone doesn’t understand you.

What to do instead:

Learn a few basic Japanese phrases: “Konnichiwa” (Hello), “Arigato gozaimasu” (Thank you), “Sumimasen” (Excuse me/Sorry), “Hai” (Yes), “Iie” (No), “Wakarimasen” (I don’t understand). Even attempting these will be appreciated. Speak slowly and clearly. Use gestures, point to maps, or use a translation app on your phone – these are invaluable tools. Be patient and polite. Many Japanese people will go out of their way to help you, even if there’s a language barrier. Having your hotel address written in Japanese can also be a lifesaver for taxi rides.

12. Queuequette: The Unspoken Law of the Line

Japan is the land of orderly queues. Whether it’s for a popular ramen shop, a train, or even an escalator, people queue patiently.

-

DON’T: Cut in line. This is considered extremely rude and will draw negative attention.

-

DON’T: Crowd the entrance of a shop or train door; look for the designated queuing lines or areas.

What to do instead:

Always look for the end of the queue and join it. If you’re unsure where the line starts or ends, observe others or politely ask. On train platforms, you’ll often see markings indicating where the train doors will open and where to line up. Escalator etiquette is also common: in Tokyo, stand on the left, walk on the right; in Osaka, it’s generally the reverse (stand on the right, walk on the left). Observe what others are doing. Patience and orderliness are highly valued.

A Final Thought: Embrace the Learning Curve

Japan is a country that rewards observant and respectful travellers. Don’t let this list of “don’ts” overwhelm you. The most important thing is to approach your journey with an open mind, a willingness to learn, and a respectful attitude. Japanese people are generally incredibly kind, helpful, and understanding, especially towards foreigners who are visibly trying to respect their customs.